October's pooch—m.a.d....

..."Machine Appliqué dog," that is—

And October 1976 had a dual celebration—

Wednesday, October 1, 2014

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Divided Attention

|

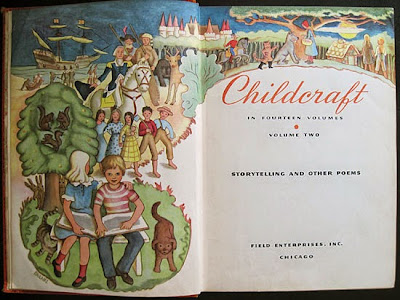

Childcraft (v 2): Storytelling and Other Poems |

Fields Enterprises (headed by an heir to Marshall Field) had moved into publishing by buying The Chicago Sun in 1944. From 1945 to 1978 the company owned the World Book encyclopedia. It seems the Childcraft series also was marketed by encyclopedia salesmen.

Other titles in series.

Endpapers—

The text has at least one illustration for page, with a single artist illustrating a 2-page spread. As a number of different artists are represented, the book is interesting for variations in period styles aimed at children.

Text is grouped in three sections: "Poems for Everyday," "Humorous Poems," "Storytelling Poems and Ballads."

Near the end is this colorful spread—

Patriotism here—

Followed by some broadening of the sales market—

I'll have to get to more illustrations in future, but another item of interest for now is an item left in the book. It would seem that around the 1980s, this copy was handed down to a child with more up-to-date daydreams than those the Fields Co. promoted—

|

| Page from a tear-out sticker book (to scale) |

Monday, September 1, 2014

Wednesday, August 20, 2014

Under the Blue, White and Red

In a jumbled pile of thrift shop scarves J. spotted this bit of history—

During World War II, clothing manufacturers used rayon to replace unavailable silk. Although the European war didn't end until May 8, 1945 (VE Day), this scarf might have been made any time after the August 25, 1944 liberation of Paris it commemorates.

This month happens to mark the 70th anniversary. The distance is evident in France's political swings to the right, and in the latter's usual efforts at re-writing history.

But this scarf represents an historic moment in Paris, 1944.

From Sacré-Coeur at the city's highest point—

The steps of Montmartre sweep down to a city full of flags, banners, and jubilant cartoon characters.

The whole scene surrounded by victory slogans—

"Vive Les Sammies"—

This was a new one on me, and I didn't get it. But (as usual) J. did: "Sammies" for "Uncle Sam." This appears to date from World War I, when it was used by both French and British soldiers.

There doesn't seem much to be found (even in French) on designer Denise Louvet.

But the textile house was well-known. Its trademark, the Place Vendôme Column, denoted the shop's Paris location.

Some period ads are here. This is the shop in 1937—

The patriotic color schemes of these ads are from 1945—

By an interesting coincidence, J. found this scarf just after I had read Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States. The book was published in conjunction with this exhibit, curated by author Jacqueline Atkins.

It was fascinating to see how the French scarf continues the British and American war-time theme of morale-boosting messages printed on textiles. The chapter in Atkins' book devoted to English scarves, "London Squares," is written by graphic design collector and historian Paul Rennie. Rennie has a pdf of the material posted here. Illustrations are unfortunately small and low resolution, but Rennie's text offers some interesting social history of wartime Britain as background to propaganda scarf manufacture.

With their increased wartime presence in factories, women were admonished to cover their hair for safety—

Rennie writes that—

Two English design houses of note, Jacqmar and Ascher, produced "up-market" scarves. Rennie offers some fascinating social background—

Jacqmar's graphic style was one of

"Jacqmar Presents" featured catch phrases of BBC radio programs—

This collector suggests that, at war office request, Jacqmar did subtle pro-French propaganda with this—

It's hard to beat those colorful, clever peintures. Still, J's scarf was an amazing find, with an historic moment expressed in period graphic style.

The perfect souvenir for a Sammie in post-war France to bring home.

|

| Rayon scarf, app. 69 cm by 71 cm (27 by 28 ") |

|

| Photo: Robert Capa |

But this scarf represents an historic moment in Paris, 1944.

From Sacré-Coeur at the city's highest point—

The steps of Montmartre sweep down to a city full of flags, banners, and jubilant cartoon characters.

The whole scene surrounded by victory slogans—

"Vive Les Sammies"—

This was a new one on me, and I didn't get it. But (as usual) J. did: "Sammies" for "Uncle Sam." This appears to date from World War I, when it was used by both French and British soldiers.

There doesn't seem much to be found (even in French) on designer Denise Louvet.

But the textile house was well-known. Its trademark, the Place Vendôme Column, denoted the shop's Paris location.

Some period ads are here. This is the shop in 1937—

The patriotic color schemes of these ads are from 1945—

By an interesting coincidence, J. found this scarf just after I had read Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States. The book was published in conjunction with this exhibit, curated by author Jacqueline Atkins.

It was fascinating to see how the French scarf continues the British and American war-time theme of morale-boosting messages printed on textiles. The chapter in Atkins' book devoted to English scarves, "London Squares," is written by graphic design collector and historian Paul Rennie. Rennie has a pdf of the material posted here. Illustrations are unfortunately small and low resolution, but Rennie's text offers some interesting social history of wartime Britain as background to propaganda scarf manufacture.

With their increased wartime presence in factories, women were admonished to cover their hair for safety—

| ||

Poster: F. Kenwood Giles, 1941 |

The scarf became, in the context of war work, an important element in safety awareness and part of the proper uniform of the female industrial workforce. These fashion notes were further emphasised through a discourse of make-do-and-mend and also in the pages of the fashion press. The pages of "Vogue" championed the active participation of women in the war effort and ran features on work wear and propaganda textiles.(Some material on British Vogue's work at the behest of the government is here.)

Two English design houses of note, Jacqmar and Ascher, produced "up-market" scarves. Rennie offers some fascinating social background—

The designs produced by Jacqmar are unashamedly aimed at an economy of exchange between wartime sweethearts in London. The existence of designs aimed at American personnel, the Free French and Poles in London serve as a reminder that, whatever the official line, fraternisation between these different groups was popular. The existence of these textiles is evidence of a social transformation in London during WW2. The pursuit of an export market as a national priority during and after the war placed a premium of these products at home. The company office in Mayfair identified the products and brand as high class, as did the relatively expensive price point of the products.(A friendship scarf example from the Imperial War Museum, along with other collection links, is here.)

Jacqmar's graphic style was one of

... dynamic and expressive line drawing. The inexact registration of colour blocks over the line give a pleasing looseness to the design and hint at "cubist" influences.This short piece includes a nice slide show of Jacqmar samples from another collector. Even when scarf designs featured such text as war-time slogans, Jacqmar's style was particularly jaunty. This one was manufactured after the US had joined the war—

"Jacqmar Presents" featured catch phrases of BBC radio programs—

This collector suggests that, at war office request, Jacqmar did subtle pro-French propaganda with this—

It's hard to beat those colorful, clever peintures. Still, J's scarf was an amazing find, with an historic moment expressed in period graphic style.

The perfect souvenir for a Sammie in post-war France to bring home.

Friday, August 1, 2014

Twelve Ways to Decorate a Dog: August

Patchwork pooch—

His exciting "pattern of textures" explained here—

On the agenda side of the month—

And there's this important official reminder—

Saturday, July 19, 2014

Problem Solved (In Under 100 Pages)

Young Adult fiction, 1974—

Full of '70s problems, for this California family. Parents' divorce, father's remarriage and suicide are the background. The current problem: 11-year old Chloris can't accept the loss of her father, and chooses to believe in a rosy past unlike the family's real history. And she's mad at her mother, who not only dates men as the novel opens, but has—a mere 59 pages later—married a widowed Mexican artist.

The new step-father: "Fidel Mancha"—as in Man of La ...

Faithful, indeed: Fidel's quest will be not against windmills, but to break through to Chloris, and end her increasingly dangerous behavior.

As described by the narrator, 8-year old sister Jenny, Fidel is a man of infinite patience, folk wisdom, and—

Jenny's openness to Fidel is used to introduce issues other than step-parenting—

Fidel's sense of justice also leaves him unimpressed by money. He makes art that interests him, selling if he chooses. When he buys Choris gifts he knows she's longed for, the gifts get "lost," or turn up damaged beyond use. When Jenny tells him he's wasting his good money, he laughs that money isn't important, it's what a person feels inside that counts. Jenny's reaction—

I assumed "gy" was meant to be "gee," in a guise somehow more '70s What's Happening Now (a bit like the spelling, "phat," decades later). But Platt has one of the mother's pre-page 59 suitors ask the girls what's that word they keep using—

Big belly aside, Fidel's character verges on romance novel wish-fulfillment; after all, what unattached gal wouldn't be attracted to such a wise, kind, teddy bear of a guy? And what hurting step-child wouldn't eventually warm to him? Never mind Chloris' attempt to burn down his studio; by the end, Fidel's sensitivity to her feelings, as expressed in his art, will reach her. Then she can stop being, in Jenny's words, "the biggest creep of all." All achieved from Fidel's introduction at page 59, to the conclusion at page 156.

Followed by these ads: more YA titles and authors I've never heard of.

The second two seem pretty much forgotten. But Donovan's book was reissued in 2010, and is considered the first YA general reader fiction to present a same-sex relationship between protagonists.

But I do remember this author and title—something for the 1970s adult reader—

Full of '70s problems, for this California family. Parents' divorce, father's remarriage and suicide are the background. The current problem: 11-year old Chloris can't accept the loss of her father, and chooses to believe in a rosy past unlike the family's real history. And she's mad at her mother, who not only dates men as the novel opens, but has—a mere 59 pages later—married a widowed Mexican artist.

The new step-father: "Fidel Mancha"—as in Man of La ...

Faithful, indeed: Fidel's quest will be not against windmills, but to break through to Chloris, and end her increasingly dangerous behavior.

As described by the narrator, 8-year old sister Jenny, Fidel is a man of infinite patience, folk wisdom, and—

He is the happiest man I ever met. He is always laughing. When he isn't laughing, he sings or whistles.Quite the catch—

Mom walked smack into the gallery that was exhibiting his paintings and sculpture pieces. She liked everything she saw, she said. Mr. Mancha was there, too, as most of the artists are at opening nights of their exhibitions. They got to talking to each other about this and that and discovered they had a lot in common. According to Mom, she didn't think about him being Mexican, one way or the other. All she saw was a very talented, big-hearted, good-natured human being. She found out he was a widower, and he found out she was a divorcee, and that was the beginning of everything.On the other hand, to make him a bit less than super-human, "he has a big belly that swells out over his silver belt buckle."(Unless the belly and silver meant as details making him an extra-jolly Mexican ...)

Jenny's openness to Fidel is used to introduce issues other than step-parenting—

Mr. Mancha is very easy to talk to and one day I asked him how come there were so few Chicanos at school, and what did they do to get out of it. Mr. Mancha explained that most black and browns were poor and couldn't get good jobs. That was why they couldn't afford to live in good neighborhoods like ours and go to our good school.Mother and daughters soon move to Fidel's place, so he can be near his studio. The house (of course) is charming and artistic, in the natural surroundings of a peaceful canyon. The new setting lets Fidel school the girls on California history—

"This is a very good country," he said, "but some people are not so lucky. To be born the wrong color is a big mistake."

"But that's not fair," I said. "They can't help it."

Mr. Mancha smiled.

...

"So, how come?"

"Don't forget the Indians," Mr. Mancha said. "I think maybe they are even worse off."

"That's different," I said. "Indians used to scalp people. They attacked our wagon trains. They scalped all the helpless women and children."

Mr. Mancha looked puzzled. "Where did you hear that?"

"I saw it myself on TV"...

Mr. Mancha nodded and pursed his lips and didn't say anything. He didn't seem convinced. Maybe he's so busy painting pictures that he never gets to watch TV and you can miss a lot that way. I've probably seen over a hundred Indian massacres already and I'm only eight years old.

"All this land you are sitting on now... was once owned by Mexicanos. From here to the sea. Up north past Malibu and Santa Barbara. And Orange County, too—Yorba Linda, where our President was born—all California was Mexicano. They were the real Californios."When Jenny asks how come, Fidel elucidates for a page and a half: missions and ranchos, land grants and treaties. Choris ostentatiously goes to her room, but Jenny wants to stay and hear the end.

"That's the whole story, little one. From now on, when you hear of some poor chicano complaining about how he is being treated, you will understand why. There was a time when he was somebody in this country."Well, it's really not a bad treatment for young readers, even if Platt can lay things on thickly, between the lessons and the dialog he gives his 8-year old.

I stood facing him, "I don't have anything against the chicanos, Fidel. And remember, I didn't take their land away from them. I'm only eight years old."

Fidels's laughter followed me all the way upstairs.

Fidel's sense of justice also leaves him unimpressed by money. He makes art that interests him, selling if he chooses. When he buys Choris gifts he knows she's longed for, the gifts get "lost," or turn up damaged beyond use. When Jenny tells him he's wasting his good money, he laughs that money isn't important, it's what a person feels inside that counts. Jenny's reaction—

I looked up at Fidel, kind of disgusted. Had he had all those hundred thousand acres given to the original Don Bernardo Yorba during the Mexican reign, he would have given them all away if he felt like it.Yup: Jenny's narration does tend to be on the overly precocious and omniscient side. Though when the sisters speak with each other, Platt inserts slang—both period ("Right on!"), and—well—odd (they constantly exclaim, "Gy!")

I assumed "gy" was meant to be "gee," in a guise somehow more '70s What's Happening Now (a bit like the spelling, "phat," decades later). But Platt has one of the mother's pre-page 59 suitors ask the girls what's that word they keep using—

Mom answered for me. "The kids use it nowadays the way we used "Gee,' 'gosh' or 'golly.' They shortened it to Gy, pronounced Guy."The laboriousness of this gives me the feeling that "Gy" was not exactly on everyone's lips. Perhaps the author was trying to invent Valley Girl speak, a few years ahead of its time?

Big belly aside, Fidel's character verges on romance novel wish-fulfillment; after all, what unattached gal wouldn't be attracted to such a wise, kind, teddy bear of a guy? And what hurting step-child wouldn't eventually warm to him? Never mind Chloris' attempt to burn down his studio; by the end, Fidel's sensitivity to her feelings, as expressed in his art, will reach her. Then she can stop being, in Jenny's words, "the biggest creep of all." All achieved from Fidel's introduction at page 59, to the conclusion at page 156.

Followed by these ads: more YA titles and authors I've never heard of.

The second two seem pretty much forgotten. But Donovan's book was reissued in 2010, and is considered the first YA general reader fiction to present a same-sex relationship between protagonists.

But I do remember this author and title—something for the 1970s adult reader—

Tuesday, July 1, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)