For one thing, modern marketing and consumption habits make disposable packaging ubiquitous. And in a country where presentation is so important, each cookie in a box is likely to be wrapped individually. When I lived in Japan in the mid-1980s, I also learned that you have to speak up fast, before the book store clerk wraps the magazine you've just bought to read on the train.

Japan is a country where packaging is an art, and traditional wrapping can be both artful and reuseable. The practice of carrying furoshiki is being encouraged again by Japan's Ministry of the Environment.

And Japanese are very recycling conscious: a point American right-wing pundits— shameless as ever—used in mocking tsunami survivors.

Food tins are one type of packaging that can be reused as storage containers, if not put out with the recycling. For me, the designs on Japanese tins made it hard to part with any I acquired.

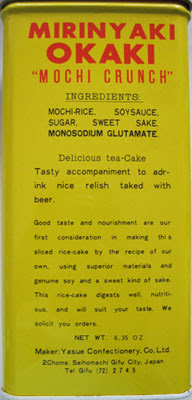

It was in the U.S., though, that I found this sembei tin—at a Seattle Buddhist church rummage sale, late in the 1990s.

The color scheme seems to be from the 1970s. If that's right, the tin was likely reused for twenty or more years before it came my way.

The color scheme seems to be from the 1970s. If that's right, the tin was likely reused for twenty or more years before it came my way.The post-war urge to decorate things with English (or the appearance of English) is also on display here.

In this case, English seems not a matter of flashy marketing but of eagerness to inform buyers of the product's great virtues:

In this case, English seems not a matter of flashy marketing but of eagerness to inform buyers of the product's great virtues: MIRINYAKIThe text may have been written for the tin. Or it may have done double duty, as it sounds like it could have been part of a letter pitching the product to foreign distributors.

OKAKI

"MOCHI CRUNCH"

...

Delicious tea-Cake

Tasty accompaniment to adr-

ink nice relish taked with beer.

Good taste and nourishment are our

first consideration in making this

sliced rice-cake by the recipe of our

own, using superior materials and

genuine soy and a sweet kind of sake.

This rice-cake digests well, nutri-

tious, and will suit your taste. We

solicit you orders.

The earnestness does seem quaint because, by the 1980s, English words and phrases connected to products and marketing were pretty much decorative. When there was a vogue for the word "communication," there were "Chocolate Communication" candy bars, "Bread Communication" bakeries, and more.

Some products have designs incorporating longer pieces of text. These sometimes start off sounding fluent; but then... To quote a tee-shirt from around 1985:

It is imperative that the rising generation master at least one foreign language. I like study Engrish.Sometimes I saw products with sentences or paragraphs in a Romance language, French being most common. To me (and my high school French ability), those examples seemed far more grammatical than the usual English on products—I think because those texts were likely lifted from some printed source.

It was the seemingly literary passages, appearing in strange, out of context uses, that was so striking.

My favorite example is this cake tin...

... and the tale it tells:

My translation:

My translation: She never went out. She would rise each morning at the same time, look at the weather from her window, then sit down before the fire in the room.Taken from a literary rendering of upper class ennui?

When she had finished her meal, she went to the window and looked at the Rue de Seine, full of people.

A sad story; and yet, it seems quite grammatical.